By Shannon Melnyk, Special to the Sunday Province

Dan Singh Kadhka being led by his son after cataract surgery

BAJURA, NEPAL — “I feel like a dog. My wife treats me like a dog.” Dan Singh Kadhka is an 80-year-old blind man who lives more than 12,000 kilometres away from B.C. But his life is about to change largely due to a Vancouver-based organization dedicated to reaching the unreachable.

From a global perspective, Kadhka is considered the poorest of the poor. The forgotten. He has been living a life of abject dependence since losing his sight five years ago. He sits in the dark in one of the most isolated, impoverished villages on the planet. He lives in Bajura, Nepal, a stunning but unforgiving landscape he has not seen for five years. Kadhka learned that some eye doctors were coming for a special visit. So he decided to make the perilous, four-hour journey on foot from his home in a neighbouring village to the village of Martadi, with only his memory and his stick to guide him.

He’s in the tiny, dusty one-room home of his third son, describing what it’s like to have bilateral cataracts. His left eye is inoperable due to an injury to the lens left too late. For his right eye, surgery will offer some hope. He has been unable to farm and is cared for by his wife, Nanda. He admits wanting to die but also hints at some optimism.

“What if I die, it’s fine,” he says. “But I want to see.”

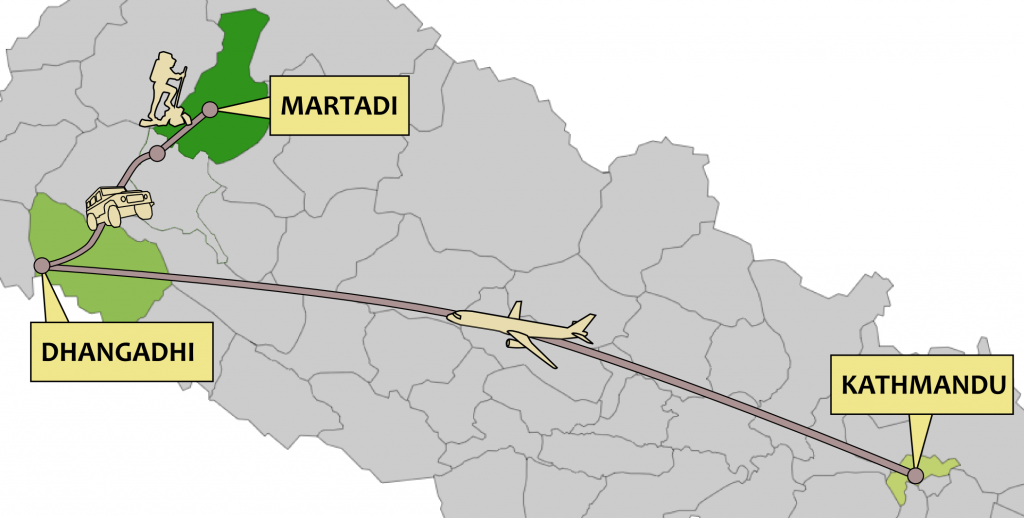

The visitors he’s hoping can help him have been travelling for three days. Their 1,120-kilometre journey from Kathmandu, over treacherous elevations and rocky, motion-sickness-inducing roads, ends with a 20-km hike and a laborious climb up a mountain in unfathomable heat. Elation prevails over exhaustion as the crew reaches the top and wades through a goat stampede and curious villagers to reach the site that will mark a historical accomplishment.

LIFE-CHANGING FOR BAJURA

On this day in May, Vancouver-based Seva Canada has arrived in the western district of Bajura to open a primary eye-care centre and hold a surgical camp that will be life-changing for an entire community. “Let’s get to work,” chirps a tireless Penny Lyons, Seva’s executive director. Lyons has spent the last seven years travelling back and forth from Vancouver to remote locations in 11 countries. For Seva, a small Canadian NGO that has been working more than 30 years to eradicate preventive blindness in Nepal, Bajura holds much significance: It’s the last region in the country without access to eye care. In a matter of days, the inauguration of the centre will mean Seva, its donors and the people of Nepal will realize their longtime dream to establish a primary eye-care facility in every region of the country. Over the next 72 hours, Seva will oversee a small team that includes two Nepali surgeons and a handful of support staff who will screen almost 800 villagers.

Bajura line-up for registration at the eye camp

By 6 a.m. on the day after the team’s arrival, patients line up for registration. By the afternoon, 43 of them, including many who have been blind for years, will receive dramatic yet simple cataract surgeries that will restore their sight by the next day.

Kadhka is asked what he will want to see when his sight is restored. “Everybody,” he says with a smile. Ninety per cent of the blind live in low-income countries such as Nepal, where 16 per cent of the population suffers from eye disease.

“Everybody,” he says with a smile.

NEPAL BLINDNESS INCREASING

Blindness is increasing in Nepal at an alarming rate, mostly caused by cataracts, followed by trachoma, glaucoma and simple infections. Poor sight is synonymous with poverty, a debilitating cycle especially tragic as most cases are preventable and curable. ]

Seva (Sanskrit for “selfless service”) focuses on eye care because it has a profound and immediate impact on relieving suffering, enabling children to go to school and adults to work, breaking poverty cycles and creating a ripple effect for the future of families of the developing world. “A $50 donation essentially covers one cataract surgery — that’s a huge bang for your buck when you consider how many lives one surgery changes”, says Lyons. “The impact is immeasurable. The patients have their lives back, their caregivers have their lives back. It gives families a chance in an otherwise dismal set of circumstances, especially in these remote communities . . . these people have nothing.” A solvable crisis.

A big part of what Seva has learned is that when communities are as remote and poor as Bajura, the key to preventing and treating eye disease is access. Poverty has prevented most of these people from being able to make the two-day journey to the closest eye centre. Located in the Seti zone of Nepal, Bajura offers stunning landscapes but an unforgiving way of life. It has one of the lowest literacy rates in the country, and HIV in almost every household. Conditions are so difficult, most men in Bajura make the long trek to India for months at a time to find work. A mudslide in the area claims two lives shortly before Seva arrives. Not long after the centre opens, the bodies of three children are carried through the village after mushrooms foraged for a meal turn out to be poisonous. Early deaths are a given here. The average life expectancy is 50 years.

Vancouver’s Dr. Ken Bassett roams the grounds looking in the eyes of children and discussing cases with the Nepali doctors. Bassett has been Seva’s program manager for 15 years. He is also a University of B.C. professor of medicine and director of a research program in international and epidemiologic ophthalmology. He says if the support continues for the Seva model of care, the suffering of people like Kadhka will one day disappear. “The measure of success is preventing versus treating. As a result of permanent primary eye-care centres, it will be a rare sight to come across these people who have suffered blindness for years,” says Dr. Bassett. “You don’t see Canadians blind from cataracts. It’s all about access, and we’re a facilitator, funder and catalyst for local partners who know where the needs are and can retain professionals in these remote areas. “We aren’t an NGO that swoops in, does some surgery and leaves. “The research and the work Seva has done shows that a long-term investment in local programs with an emphasis on training is everything when it comes to creating a sustainable model that works.”

Patients sit outside a primitive stone building that has been turned into a sterile operating room, waiting for their turn. Inside, two single beds are pushed together and four pre-op patients lie horizontally. Two surgical beds are only steps away, where Dr. Bidya Prasad Pant, an ophthalmologist and director of a Seva partner hospital, methodically accomplishes 43 of the 64 total procedures in a matter of hours. Pant, 49, is a Seva living legend. He has conducted a whopping 100,000 cataract surgeries in his lifetime — many in eye camp settings in remote areas without a hospital.

Dr. Pant with a cataract patient after a successful operation

A SEVA LIVING LEGEND

It’s an even more impressive number given that the low complication rates of these surgeries are comparable to, if not better than, those performed in Canadian hospitals. Pant has been able to accomplish so much thanks to the Seva model. In addition to donations, funds for the surgeries come from patients who can afford to pay, which helps to cover the primary eye care and surgeries of those who can’t pay. Bandaged hopefuls wait patiently Kadhka emerges from surgery with a bandage and a glimmer of hope. His son carries him home for some rest before his bandage is removed the next day.

Dan Singh Kadhka thanking the team

In less than 24 hours, a sea of bandaged hopefuls sits patiently on the grass waiting for the big reveal. One by one, their bandages are taken off and expressions of wonder take hold. They’re each issued antibiotics and sunglasses to wear temporarily. All of the surgeries are successful and Kadhka is overcome with emotion. This time he walks home on his own two feet, accompanied by his son, and reflects on the possibilities of what is instantly a new life. He says he’ll be happy to see his wife and is overwhelmed to be able to see his son. To the people of Seva he says: “If there was a God he would have opened my eyes before, but it is you who have opened my eyes.” Despite Seva’s inroads, many Canadians have not heard of the little NGO on a massive mission. The organization goes about its campaigns quietly, but Bassett says they’re willing to get a little louder in order to continue their work. “I guess we’re typically Canadian”, he muses. “We want the partners to get the glory.” Even in a world where 284 million people have visual impairment, Bassett says we could see the eradication of preventable and treatable blindness within 10 years if capabilities and resources were utilized to their full potential. The benefits would trickle down and create more economically independent nations, he says.

PROGRAM SPREADS TO TIBET, INDIA, MALAWI AND OTHERS

The model that began in Nepal so many years ago is also underway in Tibet, India, Malawi, Guatemala and many other countries. It’s the same model that’s been lauded by the international humanitarian community. Dr. Muhammad Yunus, founder of the Grameen Bank and Nobel Peace Prize recipient, admires Seva’s sprit of innovation. “They aren’t afraid to try something that no one has ever tried before,” he has said. As far as promoting awareness and encouraging more Canadians to contribute, Bassett says: “It’s really important. We just haven’t had time. We’re so busy and there’s so much to do.”

A volunteer’s empowering vision “Pure addiction” is how Nanaimo-based ophthalmologist Dr. Marty Spencer describes his work as a Seva volunteer. The award-winning surgeon has been training doctors in seven developing countries and creating innovative eye care techniques since the early 1980s. Seva Canada credits Spencer as one of the first doctors in the world to set up eye camps in remote areas and with pioneering sutureless cataract techniques and surgical instruments that could be used in remote, challenging environments. Spencer also played a key role in the creation of Aurolab, a non-profit manufacturing facility in India that enables low-cost production of intraocular lenses, making surgery affordable in poor countries and transforming the way eye surgery is done in the developing world. Of the recent accomplishment in Bajura, Spencer says he is incredibly proud of Seva’s partnerships in Nepal, where he got his start with the non-profit. “That country is so close to my heart,” Spencer says. One of the most emotional moments he experienced during one of his many visits was the reaction of a blind mother who was able to see her two-year-old for the first time. “She said, ‘You have given me divine sight,’” recalls Spencer. “The work we are able to do is that inspiring, all of the time.”

EQUAL CARE FOR GIRLS AND WOMEN

Two-thirds of the world’s blind are women and girls, but they’re only treated half as often as men and boys It’s a staggering inequity that was revealed by a UBC international study over a decade ago that included Seva’s Dr. Ken Bassett as a lead author at the B.C. Centre for Epidemiologic & International Ophthalmology. After the study’s findings, Seva Canada made it a priority to help close the gap. “Most eye programs in the world were unaware of this bias and surprised by this finding”, says Bassett. “They simply looked at the total numbers. We taught them all to go back and look at their numbers again. As a result, the eye care world changed to focus on women.” Bassett asserts gender inequity in eye care reflects the vast overall inequities for women in most of the world. Cultural and economic barriers that prevent women and girls from receiving eye surgery include issues such as costs and the inability to travel. He notes, however, that the most profound factor is a lack of access to knowledge. As a result, Seva and their partners focus heavily on advocacy, tailoring outreach programs to women and targeting women’s community groups for education and assistance.

SEVA CANADA’S ROOTS

Vancouver-based Seva Canada evolved out of the Seva Foundation, a U.S. grassroots movement in the 1970s that was inspired by the World Health Organization’s successful campaign to eradicate smallpox. In 1978, Dr. Larry Brilliant and his wife Girija Brilliant, who had participated in the smallpox drive, convened a conference of friends and colleagues — including the curious cross-section of the Grateful Dead’s Wavy Gravy, contemporary spiritual figure Ram Dass, and the World Health Organization’s Dr. Nicole Grasset — to determine their next goal. Dr. Grasset introduced the group to Dr. G. Venkataswami, a retired eye surgeon in India whose vision was to make cataract surgery as “ubiquitous as McDonalds,” and therefore affordable to the poor. So began the Seva Foundation, which works with global partners to operate its sight program. Vancouverites Alan Morinis and Bev Spring, who were among the Seva Foundation’s board members, decided to develop support for Seva’s work in Canada and engaged Canadian government support and funding.

Seva Canada was incorporated in 1982. Today, Seva’s Vancouver operations are comprised of five staff members, 13 board members, three honourable patrons and 13 regular volunteers. Seva Canada receives more than 50 per cent of its funding from individual and corporate donations; 12 per cent comes from the Canadian government; 10 per cent from foundations and grants and the rest from fundraising events and donations of equipment. © Copyright (c) The Province